About Bolin Creek

Maps,GEOLOGY, HISTORY,

plans & Studies

Maps, Geology, History, Plans & Studies

Geology

Click here to learn more the Geology of Bolin Creek.

This information was prepared by Phil Bradley in an effort to help facilitate earth science education in the Chapel Hill – Hillsborough, NC area. The website conveys general geologic principles with examples from the “backyard” of the residents of Chapel Hill, Carborro, Hillsborough and Durham, NC areaPhil Bradley is a Senior Geologist with the Geological Survey and Program Supervisor for Piedmont Geologic Mapping.

History

This history contributed by Mark Chilton and Matt Longnecker.

Origin of the Name ” Bolin” Creek

Beginning in the 1740’s, European settlers began moving into the area that is now Orange County, NC. By 1752, there were enough settlers here that the Colonial government saw fit to create a new county, named in honor of King William and Queen Mary, for he was known as William of Orange. At that time, the entire Bolin Creek watershed (as well as 14% of the entirety of North Carolina) was owned by a man name John Carteret, the Earl Granville ‘ at least that was how the situation was viewed by the Europeans. Granville sold many large parcels to real estate speculators and settlers including a grant of several hundred acres to a man named Benjamin Bolin. Bolin bought land in the vicinity of University Mall and the creek that ran through the property came to be known as Benjamin Bolin’s Creek. Some old records call it Ben’s Creek, but most call it Bolin’s Creek. Back in that day, spelling was highly variable, so sometimes the name was spelled Bolling, Boland, Bowlin or other variations. Whatever the spelling, the name stuck and it is still known as Bolin Creek today.

The Mills of Bolin Creek

Castleberry-Taylor Mill

Of the four old water-powered mills that stood on Bolin Creek, the best preserved is the former Castleberry-Taylor Mill. The ruins of the mill, millrace and dam are just upstream of the Spring Valley neighborhood in Carrboro. The stone foundation of the mill is still quite discernable, but just 30 years ago some of the walls were also standing. On November 1, 1763, the Orange County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions granted permission to William Castleberry to “erect a Water Grist Mill on Boling’s Creek.”Oral history has it that this mill once belonged to John ‘Buck’ Taylor, a noted slave driver, bad cook and drunk, who lived just west of Chapel Hill in the latter 18th century. Buck Taylor (1747-1828) was a soldier in the Continental Army, and was also the first steward of UNC, in 1795. The first students of UNC objected vociferously to the inadequate quality and quantity of food he provided and vandalized his property. Taylor soon quit (Ryan 2004 P 140).The November 1799 Orange County Court minutes include this: “John [Buck] Taylor Esquire appearing in open Court intoxicated with liquor and having shewn . . . great contempt to the authority of this court . . . It is commanded by the said Court that the said John Taylor be fined in the sum of ten pounds and that he be committed to close custody in the Gaol of this County until the end of this present term [about a week] .” As if that weren’t embarrassing enough, Taylor was the Clerk of Court at the time!Legend has it that Taylor was buried standing up, either with a whiskey jug in each hand or for the purpose of continuing to oversee his slaves. Taylor’s gravestone can still be seen on Buck Taylor Trail in the Cates Farm neighborhood, not far from the mill.

Yeargin Mill

The Yeargin Mill stood in what is now Umstead Park in Chapel Hill. The mill was built about 1790 or so by Benjamin Yeargin and was a local landmark for many, many years. Today you can still see the ruins of part of the dam in the form or a curious ridge of land on the western edge of the park, between the basketball courts and the Exchange Club Pool. A mill operated here through the 1800’s and the dam still stood into the early 1900’s, when it was used as a water supply reservoir for UNC. The base of the old UNC pump station can still be seen in the park. UNC President Kemp Plummer Battle writing in The History of the University of North Carolina (1907) called this area “a most romantic defile, called Glenburnie . . . along the stream on the south bank is a lovely path of countless ferns, which I name the Fern Bank walk.”

Waitt-Brockwell Mill

The Waitt-Brockwell Mill stood right below the Martin Luther King Jr. Road (Historic Airport Road) bridge in Chapel Hill. This mill was apparently built by Kendall Waitt in 1842, although there may have been other mills here before that. President Battle called this site “the Valley Mill Pond . . . once a beauteous sheet of water, a favorite for swimming and skating, and much visited by those fond of walking.” An apocryphal tale is told in Chapel Hill that the mill was abandoned after the Town built a sewer outfall on the creek just upstream of the mill, for no one could stand the smell. Today there is apparently no sign of the former mill or dam.

Morgan-Jones SawmillThe Morgan-Jones Sawmill was built before 1792 by Hardy Morgan, a son of Mark Morgan for whom Morgan Creek was named. The mill was owned for a short while by Edmund Jones, a Revolutionary War hero and major landowner in Orange and Chatham Counties. The mill stood where the old road to Oxford crossed Bolin Creek, which was about where the Franklin Street bridge is now. No ruins of this mill have been observed.

Chapel Hill Iron Mine and the Railroad

In 1872 Confederate General Robert F. Hoke bought Iron Mountain, the hill that lies between Bolin Creek, the railroad, Seawell School Road, and Estes Drive Extention. Together with his business partners, Gen. Hoke began agitating for a rail spur from University Station on the North Carolina Railroad to Chapel Hill ‘ a route that was anticipated to bring the railroad very near his iron mine. Although it took 7 years to organize, prison labor eventually built the railroad to a point just west of Chapel Hill in what would later become downtown Carrboro. In 1880, a further spur from that line was built up Iron Mountain to convey the iron ore down to the main railroad. The abandoned bed of that narrow gauge railroad can be seen today, just north of the trestle over Bolin Creek, winding up the hill into the Ironwoods neighborhood. Unhappily, the price of iron ore dropped dramatically in 1881 and by 1882 the mine closed, never to reopen. A vestige of the old mine and historic marker can be found on Ironwoods Drive in the residential neighborhood built on the site of Iron Mountain.

The Civil War

On April 17, 1865, the Union Army invaded and occupied Chapel Hill. The president of UNC parleyed with Sherman, arranging that in exchange for the surrender of Raleigh, the University at Chapel Hill would be spared from destruction. The Union soldiers who guarded UNC camped along the fringe of Chapel Hill (Ryan 2004 P 175), and it is said that they stored their ammunition in a rather unlikely spot–the shallow cave just next to Bolin Creek.

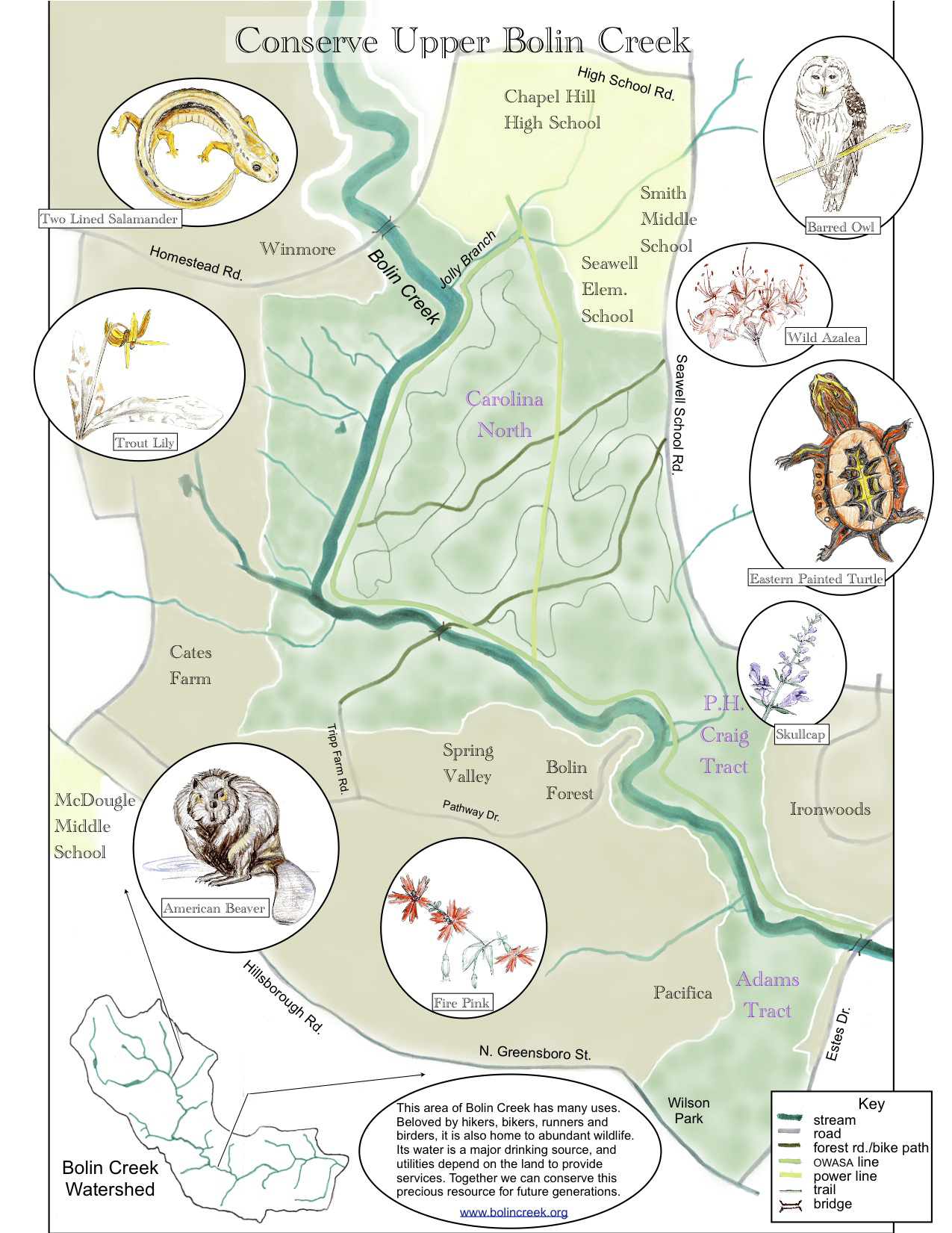

The Horace Williams Tract, now known as Carolina North, comprises more than 900 acres that are as yet largely undeveloped. Horace Williams gave this property to UNC in 1940. Bolin Creek runs through the southern part of the tract, in Carrboro. UNC plans to develop the property, though when and how remain under discussion.Henry Horace Williams was born in 1858 in Gates County, N.C., and graduated from UNC Chapel Hill in 1883. He earned the first advanced degree awarded in the college’s history (a Master of Arts). In 1890 Williams became the first Professor of Philosophy at UNC Chapel Hill; he was a professor emeritus from 1936 until his death in 1940.His biographer said of him that “no teacher of his day exerted a wider influence or had more loyal and appreciative [students] ” He had a magnetic personality and was an orator who was confident, sincere, and popular. In the classroom he favored the Socratic method. His goal as a teacher was to reconstruct and liberalize southern thought to increase tolerance, and above all, to develop principled individuals who thought clearly.

The Horace Williams House. While ‘Old Horace’ was devoted to ideals and the University, he was undiplomatic with some of his fellow faculty, and often controversial in his public and private life. He was a shrewd investor who favored real estate. The Horace Williams tract is the largest parcel he left to the University. He bought the property around 1905 when it was farmland, described as a plantation. His house, on 610 Rosemary Street, is a cultural resource and art exhibition space operated by the Preservation Society of Chapel Hill.

References:

Robert Watson Winston. Horace Williams: the Gadfly of Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1942.

Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill more biographical information about ‘Old Horace’: http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/htm/01625.html#d0e325.

Lloyd-Andrews Historic Farmstead and the Headwaters of Bolin Creek — an oral history from Jean Earnhardt supplemented by various sources.

The headwaters of Bolin Creek, which go dry some years, are about one mile south of Union Grove Church, between Union Grove Church Road and Old Highway 86. The Creek’s modest beginning is a spring that flows into a shallow depression about 2 feet wide, on the gentle eastern slope of a ridge running southwest-to-northeast. From there, the creek runs south through a gated community called Talbryn. About one mile below the headwaters, the brook has been dammed, forming a large pond.The area around the pond was once part of a 599-acre parcel that was owned by Stephen Lloyd in the late 18th century. After the revolutionary war, in 1784, when North Carolina was desperate for cash, Stephen Lloyd paid the State of North Carolina 300 shillings to register his deed and help the state raise money. Stephen Lloyd was the son of Thomas Lloyd. Thomas Lloyd was a powerful figure in Orange County politics whose business dealings in North Carolina began in the 1750s. The Lloyd family originally had come from Wales, and had been in Virginia for two generations before Thomas Lloyd was born (b. 1710, d. 1792). Thomas Lloyd owned 2,000 acres in Virginia before moving to Orange County. A monument to Thomas Lloyd is located on Stony Hill Road, about 50 feet east of Old Highway 86, just north of Calvander (the monument includes some inaccuracies due to the similar prominence of another Thomas Lloyd, who lived near the N.C. coast during the same period). Stephen Lloyd was said to have been shot to death on his ‘plantation’ by a slave named Isaac, around 1790. His property has remained in the family to this day. Sometime around 1800 a hewn log house was built on the property, about 100 yards west of the Creek. The house is one of the two oldest dwellings in the Carrboro planning district.

The part of the tract that included the old house and farm eventually was inherited by Eppie Brewer (b. 1894). She married Chesley Foster Andrews, who was from an equally old Orange County family of Scotch-Irish origin. Chesley Foster (known as C.F.) Andrews was a cousin of Calvin Andrews, for whom Calvander was named (a contraction of his name). Calvin ran an excellent school (Andrews Academy) that was located behind the Calvander BP station. C. F. Andrews prospered owing to his hard work and to the farmstead’s many assets, including cotton and tobacco. His wife, Eppie, died in childbirth in 1894. Four years later he moved his family from the log cabin to a fine farmhouse he built on Union Grove Church Road, still easily visible from the road. Mr. Andrews made weekly trips to Chapel Hill in a horse-drawn wagon until the mid-1930s, to deliver produce, dressed chickens, sausage, and pressed cakes of butter to professors at UNC. The wagon was then replaced by an A-model Ford which considerably shortened the driving time to Chapel Hill.

Eppie and Chesleys’ son, Troy Andrews, and his wife, Roberta (nee Chandler), settled on the property when they retired in 1961. They had prepared for retirement during the prior decade by restoring the old log cabin, turning the former barn into a residence, and putting in the pond on Bolin Creek in 1952. A federal program provided financing for the pond project. In the early 1950s, a young, aspiring Swiss architect, Franc Sidler, visited them by chance and learned of their plan to build a house on the farmstead. Recognizing that the outcropping of rocks west of the pond made for a natural setting for an ‘organic’ design, his subsequent class project as an apprentice under Frank Lloyd Wright was to draft the blueprints for the Andrews’ home. Thus, the Andrews built a unique home on the property in the 1960s. The walls of the house are made primarily of a light-colored lava (dacite felsite), which came from the farmstead. The lava came from a volcano that was active about 650 million years ago. The house is an architectural jewel.

Today, Troy and Roberta’s daughter, Jean Earnhardt, and her husband John live in the stone house. The Earnhardts have a large collection of American-Indian artifacts that were found on the grounds. They also have a Civil War-type miniball that was found there. The Earnhardt’s own 160 acres of the original tract, of which 120 acres have been put in a conservation easement partnered by the Triangle Land Conservancy. This property is known as the ‘Lloyd Andrews Historic Farmstead.’

Their son, David, his wife Maureen and their four granddaughters live in the old farmhouse (just off Union Grove Church Road) which has undergone a series of ‘uplifts’ during the 108 years since C. F. Andrews built it. At heart, however, it is still a typical Piedmont ‘I’ house, with a wide front porch and chimneys on both sides. Although the Lloyd-Andrews Historic Farmstead is privately owned, the Earnhardt family will show the historic property by appointment (call 929-4884). The New Hope Audubon Society holds a bird count there on New Years Day each year.

Mill ruins and Buck Taylor

Oral history has it that the old mill next to Bolin Creek belonged to John ‘Buck’ Taylor, who was famous for being a great drinker and a bad cook. In fact, Buck Taylor (1747-1828) was a soldier in the Continental Army, and was also the first steward of UNC, in 1795. The first students of UNC objected vociferously to the inadequate quality and quantity of food he provided and vandalized his property. Taylor soon quit (Ryan 2004 P 140). His gravestone can still be seen behind an eponymous street in the Cates Farm residential development, not far from here. Allegedly he was buried standing up, with a jug in each hand.

History of the Adams Preserve (by Deborah Rigdon)

The 28-acre Adams Preserve is bounded by Bolin Creek on the north and Estes Drive Extension on the east. The Preserve is a remnant of Orange County’s 18th century heritage during which time Scotch, Irish, Welsh and Quaker immigrants were welcomed as they arrived in search of inexpensive land. The original deed for the property dates from the 1780s and shows ownership by Hardy Morgan, for whom Morgan Creek was named.William Partin acquired the property in 1798. At that time the property included land near the ‘new road’ and ‘on the water of Bolands [sic] Creek’. The road was the result of construction authorized by the County Court and followed the ‘nearest and best way from Hillsborough to the University’. The ‘new road’ was to be known as Old Hillsborough Road, the remains of which still can be found on the property. By 1806, Joseph Loftin had acquired the property with its ‘attachments and appurtenances’, indicating the presence of a hewn log structure, still in existence today.In 1811, Thomas Weaver purchased the property. The land remained in the Weaver Family for over 100 years. The longstanding presence of the Weaver Family in the community is easily recognized. For example, Weaver Street and Weaver Dairy Road carry their name. The homestead, known as the ‘Weaver House’, grew in size as the farm prospered throughout the 19th century. The Weaver House was less than a mile from the small community known as West End, which in 1911 became the Town of Carrboro. The Hogan Family owned the property from 1919 until its purchase in 1941 by Sarah Watters.

In 1950, University of North Carolina Botany Professor J. Edison Adams and his wife, Katherine, purchased approximately 30 acres which includes the 28-acre Adams Preserve. The purchase included the homestead known as the Weaver House. Dr. and Mrs. Adams along with their two children, John and Martha, quickly embarked upon efforts to restore the historically significant Weaver House. The homestead, part of which was built at the end of the 18th century, is comprised, in part, of one of the oldest hewn log dwellings in the Carrboro planning district.The property passed to the stewardship of children John and Martha after the deaths of Dr. Adams in 1980 and Mrs. Adams in 1986. The untimely death of John Adams in 1992 left the management of the property in the hands of his widow, Ann Adams, and sister Martha Adams Galli. In 2004, the acreage was subdivided into 28 acres and a two-acre parcel containing the homestead. The two-acre parcel and homestead are now privately owned. In the fall of 2004, aided by a grant from the Clean Water Management Trust and taxpayer monies from Orange County’s Lands Legacy Program and Carrboro, the 28 acres were purchased as a preserve.

Dr. Adams was an internationally renowned botanist. His legacy includes authorship of the botany text, Plants, An Introduction to Modern Botany (Greulach & Adams, John Wiley and Sons, 1962). Katherine Adams is remembered by many for her kindness and involvement in numerous community activities both in Chapel Hill and Carrboro. The successful effort by Ann Adams and Martha Adams Galli to preserve the property honors the wishes of Dr. and Mrs. Adams. Future generations may now enjoy their vision and experience one of the few remaining vestiges of Carrboro’s rural and natural past.

References for the History of the Adams Preserve:

Orange County Register of Deeds (OCRD), Deed Book 2, page 386; Book 5, page 593, Book 7, page 25; Book 12, page 217; Book 14, pages 29, 121; Book 26, page 27; Book 76, page 308; Book 77, page 134; Book 114, page 318, Book 135, page 99.

Orange County Court Minutes, 1798, (no page), NC Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, NC.

Blackwelder, Ruth. The Age of Orange. Charlotte: William Loftin, 1961.

Leyburn, James G. The Scotch-Irish A Social History. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1962.

Native Americans and Bolin Creek

Evidence of Native Americans in the Piedmont goes back to 12,000 B.C. Souian tribes lived here. This area, which is in the Carolina Slate Belt, is especially rich in rocks that made good arrowheads and stone tools. Ward, an archeologist, said that ‘In almost every plowed Piedmont field some trace of [Native Americans from] the Archaic period can be found.’ (P 65), which is consistent with Friends of Bolin Creek members having found arrowheads along the creek. The Native Americans’ diet was based primarily on hickory nuts, acorns, and deer, although as late as 1701 buffalo, wolves, and elk also lived here (Ward, P 56).Pottery shards from 500 B.C. and later have been found in many Piedmont archeological sites. Permanent colonies of Europeans were established on the Carolina coast in the late 1600s and from them epidemics of smallpox spread to the Piedmont repeatedly in the 1700s (Thorton, P 79). Ryan noted that ‘in the 1700s most of the Native Americans had abandoned their former homes.’ (P xviii). Assuming that the disaster was as severe here as elsewhere in the new world, about 95% of the native population died from epidemic diseases (Diamond, P 211). One of the worst smallpox epidemics among the Native Americans in this area was in 1738; Orange County was founded in 1752.

The Andy Griffith House — an oral history from Fay DanielAndy Griffith’s career as a performer began when he lived next to Bolin Creek, in what is now Carrboro. He rented the house by the creek from 1950-1952 and signed his first professional contract there, with Capitol Records, for ‘What It Was Was Football.’ After graduating from UNC with a bachelor’s degree and a teaching credential, he taught music at Goldsboro High School for one year. Then Mr. Griffith returned to the Chapel Hill area and rented the house, which is now part of the Winmore development. The ‘Griffith House’ (1318 Homestead Road) is the second building upstream from the bridge where the creek flows under Homestead Road. (A big squarish modern house sits between the Griffith House and the bridge over Homestead Road.) When the Winmore development is completed, the house will serve as a community center for its residents. This information came from Fay Daniel, whose parents owned the house when Mr. Griffith lived there. Mrs. Daniel worked for Mr. Griffith, typing his letters during her college breaks, in 1951-1952.

References:

Diamond, Jared. Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1997.

Ryan, Elizabeth Shreve. Orange County Trio: Hillsborough, Chapel Hill, and Carrboro, North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: Chapel Hill Press, Inc., 2004.

Thornton, Russell. American Indian holocaust and survival: a population history since 1492. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, c1987.

Ward, H. Trawick. A Review of archaeology in the North Carolina piedmont: a study of change. In: The prehistory of North Carolina: an archaeological symposium, Mathis MA, Crow, JJ, eds. Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1983.

Allen EP, Wilson WF. Geology and Mineral Resources of Orange County, North Carolina. North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development, Division of Mineral Resources; Raleigh, 1968.

Plans & Studies

Plans and Studies of Bolin Creek

Majority of studies commissioned by the Towns of Carrboro and Chapel Hill and NC DENR

2003 Assessment Report: Biological Impairment in the Little Creek Watershed, DENR, Division of Water Quality.

EPA determined parts of Bolin Creek as impaired; the Town of Carrboro signed an MOA with the NC Ecosystem Enhancement Program on May 12, 2002 to conduct this study. A key finding of this baseline study established the 405+acre forest along one section of Bolin Creek as an area of special significance, worthy of preservation.

2004 The North Carolina Natural Heritage Program released a report that included the Bolin Creek natural area.

2004 Morgan-Little Creek LWP Targeting of Management Report

2004 Future of Upper Bolin Creek Corridor

2004 Morgan and Bolin Creek Local Watershed Plan

2007 Bolin Creek Watershed: Geomorphic Analysis, Earthtech

Earth Tech provided services to the Town of Carrboro during the spring and summer of 2007 to evaluate the stability of the entire Bolin Creek Watershed. This project was performed as the first step of the Towns of Carrboro and Chapel Hill as partners in the Bolin Creek Watershed Restoration Team (BCWRT) to r ehabilitate the watershed and to one day have its biological integrity improve and to the extent that Bolin Creek can be removed from the Federal (303d) list of impaired streams.

2009 Carolina North Development Agreement

This Town of Chapel Hill page contains most all relevant information. See particularly the Modifications request granted in 2013 describing the locations of the conservations areas. Final Development Agreement was based on this excellent Biohabitats, Inc. Study.

- https://www.biohabitats.com/project/carolina-north-land-stewardship-policy/

- https://facilities.unc.edu/wp content/uploads/sites/256/2015/12/1FINAL_ConsAreaDesc_REV072911.pdf

2009 Bolin Creek Greenway Conceptual Master Plan: Chapter 1,

Commissioned by Town of Carrboro

2009 Bolin Creek Greenway Conceptual Master Plan: Chapter 5,

Commissioned by Town of Carrboro

2010 Baldwin Park Stream Restoration

2010 Catena Bolin Creek Greenway Conceptual Plan Review

This report report why the Bolin Creek Greenway Master Plan did not meet its number one objective, “to improve water quality”.

2011 Tanyard Branch Study Full report

Excerpt: Tanyard Branch alternatives analysis

Excerpt: Tanyard Branch appendix

2012 Bolin Creek Situation Assessment

(WECO 2012): This study was initiated by NC DENR and the Towns of Carrboro and Chapel Hill. Professional facilitators interviewed up to a 100 participants. The Executive Summary is over 40 pages, most of it transcripts of interviews with participants. The BCWRT subcontracted part of a current EPA grant to Watershed Education for Communities and Officials (WECO), a NC Cooperative Extension program, to conduct a situation assessment in the Bolin Creek watershed. The purpose was to better understand the interests of watershed stakeholders and organizations, to identify opportunities to engage stakeholders in Bolin Creek restoration while meeting multiple interests, and to determine how stakeholders would like to participate in restoration efforts.Key recommendations of WECO Assessment:

- Create a multi organizational collaborative watershed initiative

- Examine how to more holistically plan and manage water resources

- Increase community outreach and engagement on the Carolina North Forest Stewardship Plan

- Investigate how to raise fund for water quality protection through a stormwater utility or other mean

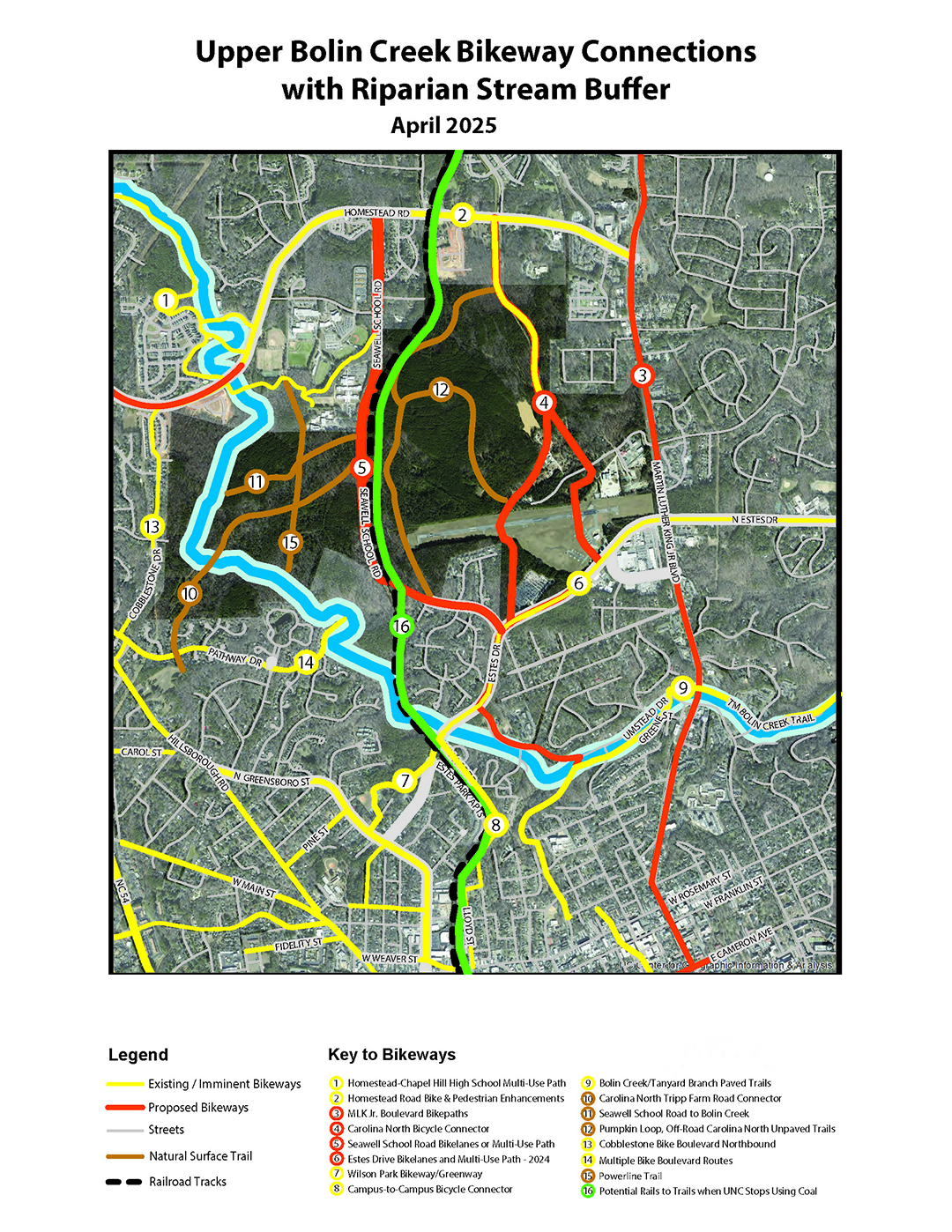

- Convene a facilitated search for bike per routes while protecting Bolin Creek’s riparian corridor

2012 Bolin Creek Restoration PlanPlan written by Chapel Hill and Carrboro staff with an EPA grant.

2012 Bolin Creek Watershed Situation Assessment

2012 Dry Gulch Stream Restoration – Town of Carrboro

2012 McDougle Middle School Bioretention Area and Cistern Installation – Town of Carrboro

2012 Monitoring Runoff from Pacifica: a Low Impact Development Subdivision

2012 Bolin Creek Restoration Plan, Towns of Chapel Hill and Carrboro

2012 Urban Stream Restoration Case Studies

2013 Bolin Creek listed on the EPA’s 303(d) list of impaired streams. The Town of Carrboro and Chapel Hill have received two Section 319 grants from the Environmental Protection Agency to develop a Bolin Creek Watershed Restoration Plan. These Section 319 grants come through the North Carolina State Division of Water Quality to fund community water quality projects.

https://www.biohabitats.com/project/carolina-north-land-stewardship-policy/

2015 Aaedan Report, funded by the U.S. Forest Service that looked at the neighborhoods of Bolin Forest and Quarterpath Trace and reported on what is needed for stewardship of this urban forest. The Aedan report, in particularly, notes on page 15 as a threat to this urban forest: “Activities such as construction of new trails or impervious surfaces have the potential to cause significant erosion and sediment run-off especially around highly erosion-prone soils with localized areas of steep slope and shallow soils located along Bolin Creek.” As a result, this study recommends to maintain water quality to “Minimize footpaths within stream corridors.”